Essential Workers: Working During a Pandemic

EvCC students discuss what it’s been like to continue working during the COVID-19 pandemic.

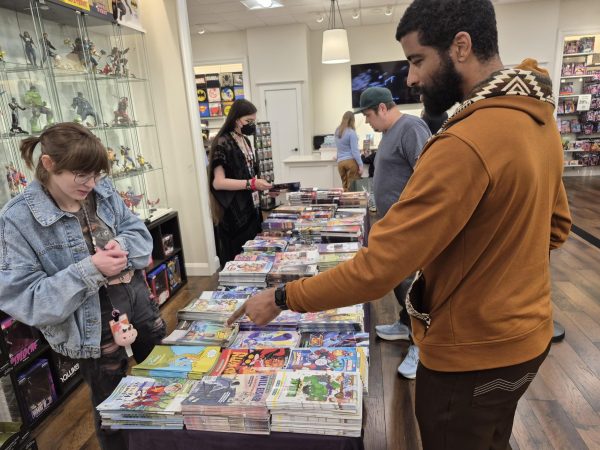

Courtesy photo from Andrea Skorheim

Nanny, Andrea Skorheim volunteers at the Everett YMCA and during quarantine has been hosting a Zoom storytime for kids every Monday at 9:45 a.m.

From childcare to retail, many EvCC students are still working hard to provide essential services to people.

For EvCC student Andrea Skorheim, who has been a nanny for twelve years, working in the midst of quarantine has been “a whole new world to navigate daily.” Skorheim currently nannies for a family with three children in Everett while working towards a degree in early childhood education.

One of the challenges she faces at her job is dealing with newfound gray areas. “As things started closing down, sort of incrementally, it was this gray area of ‘Is it safe to go to a playground? Is it safe to go to places where other people might be?’ And I just had to talk openly with my bosses and see what their feelings were and I think we all erred on the side of caution,” Skorheim explained.

Many businesses have also been airing on the side of caution by setting up safeguards to protect employees and customers alike. Some changes that have been implemented in many businesses are an hourly sanitizing of the store, required face masks and gloves on the premise and protective screens at registers. In addition to these safety precautions EvCC student Aarik Long, a 19-year-old pawnshop employee, says that one of the biggest changes at his job is “having to make sure people are staying apart because they tend to crowd each other.”

As a nanny, who lacks guidance or a set protocol, Skorheim has relied on her prior experience in the food industry and childcare centers to build her own guidelines for staying safe. “I just went with what I knew from working in daycares and working in foodservice and just applied those methods into seeing the home that they live in as a daycare or restaurant and how we would keep it clean,” she said.

Essential workers, no matter their profession, are also putting themselves at greater risk for contracting COVID-19. Long says that “It’s always in the back of your mind… but with the precautions we’re taking I’m fairly confident that we are safe.”

When stay-at-home orders were first being put into effect many people were unclear if their jobs were considered essential. Skorheim recalls the confusion saying, “There was a lot of questions and ambiguity in childcare. There are still questions and ambiguity. I had a heart-to-heart with my bosses and they are considered essential employees through their businesses… and therefore if they are essential, I am essential. I’m happy enough with that answer.”

Other essential workers have been experiencing people who do not believe their work should be considered essential. “A couple of people have been saying, ‘You shouldn’t be open.’ But then they’re still getting a coffee so they’re kind of being hypocrites,” says Peyton Nolte, a barista at Walker’s Coffee Co. in Marysville.

Some businesses, such as pawnshops, might not appear essential upon first glance. However, Long says that since they are considered a financial institute “it’s good that we are able to stay open and help people out that are struggling to get through this with being out of work and everything. We’re able to help them out and get a loan.”

Each and every person who has been deemed an essential worker continues to help people through their services. “I think that if there was anything I could shed light on it would be that there is no essential worker who is doing the job that they signed up for,” Skorheim says. “Every essential worker that I know, including myself, is doing a job much different and much greater than they ever signed a contract for.”

What interests you about journalism?

I have a passion for storytelling and journalism is one platform that I use to explore that passion. I do a...

Jo Anne Robinson • May 19, 2020 at 8:20 am

Please note your use of the word “aired.” I think you meant to use “erred.” They are not the same. Using spell check won’t catch that but your proofreader or editor should have.

Rebecca Duffy • May 19, 2020 at 12:29 pm

Thank you for pointing that out, the spelling has been adjusted!