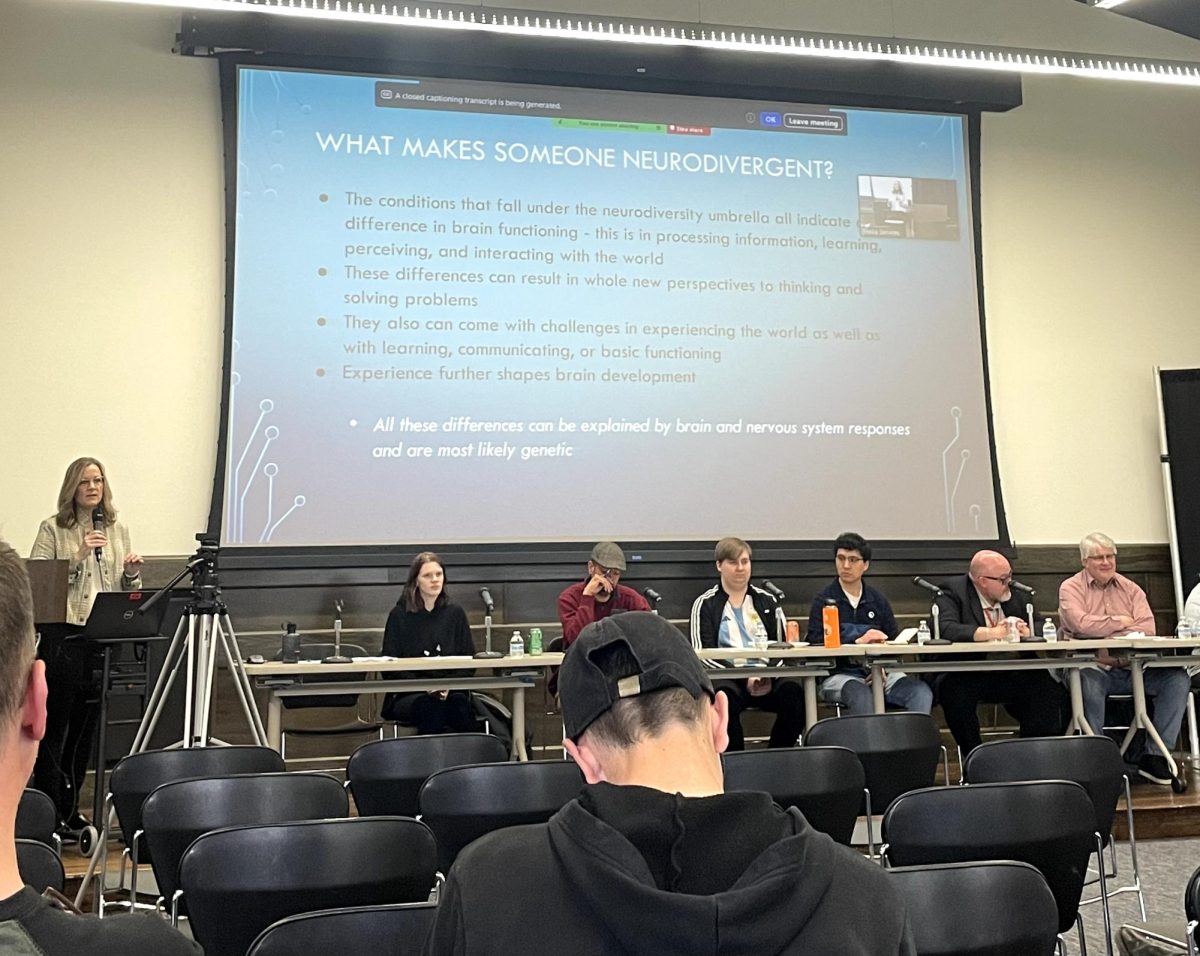

Dr. Diane Brown began EvCC’s Neurodiversity 101 event on April 25 by defining the word neurodiversity.

The term was coined by Judy Singer in 1999 and is based on the same concept as biodiversity. The conditions that fall under the neurodiversity umbrella all indicate a difference in processing information, learning, perceiving, and interacting with the world. These conditions may also come with challenges in learning, communicating or basic functioning.

Neurominority is a term that describes a group who is neurodivergent. Some conditions neurominority groups may have include Autism, ADHD, Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD), Developmental Language Disorder (DLD), Dyslexia, Dysgraphia, Tourette Syndrome, and Dyscalculia.

Dr. Brown went on to discuss the two main opposing lenses that are used to view those who are neurodivergent. The first is an outdated perspective referred to as the medical model. The medical model focuses on deficits seeking to “fix” and embrace cultural constraints. Comparatively, the new social justice model focuses on seeing barriers as the problem, seeks to empower and believes there are many acceptable ways of being.

The panel went on to discuss how being neurodivergent has impacted their personal lives and relationships, as well as their academic and professional careers and the importance of seeking accommodations to better facilitate success for themselves.

Instructor panelists Greg Prang and Omar Marquez expanded on how they design their classrooms to be inclusive of their neurodivergent students.

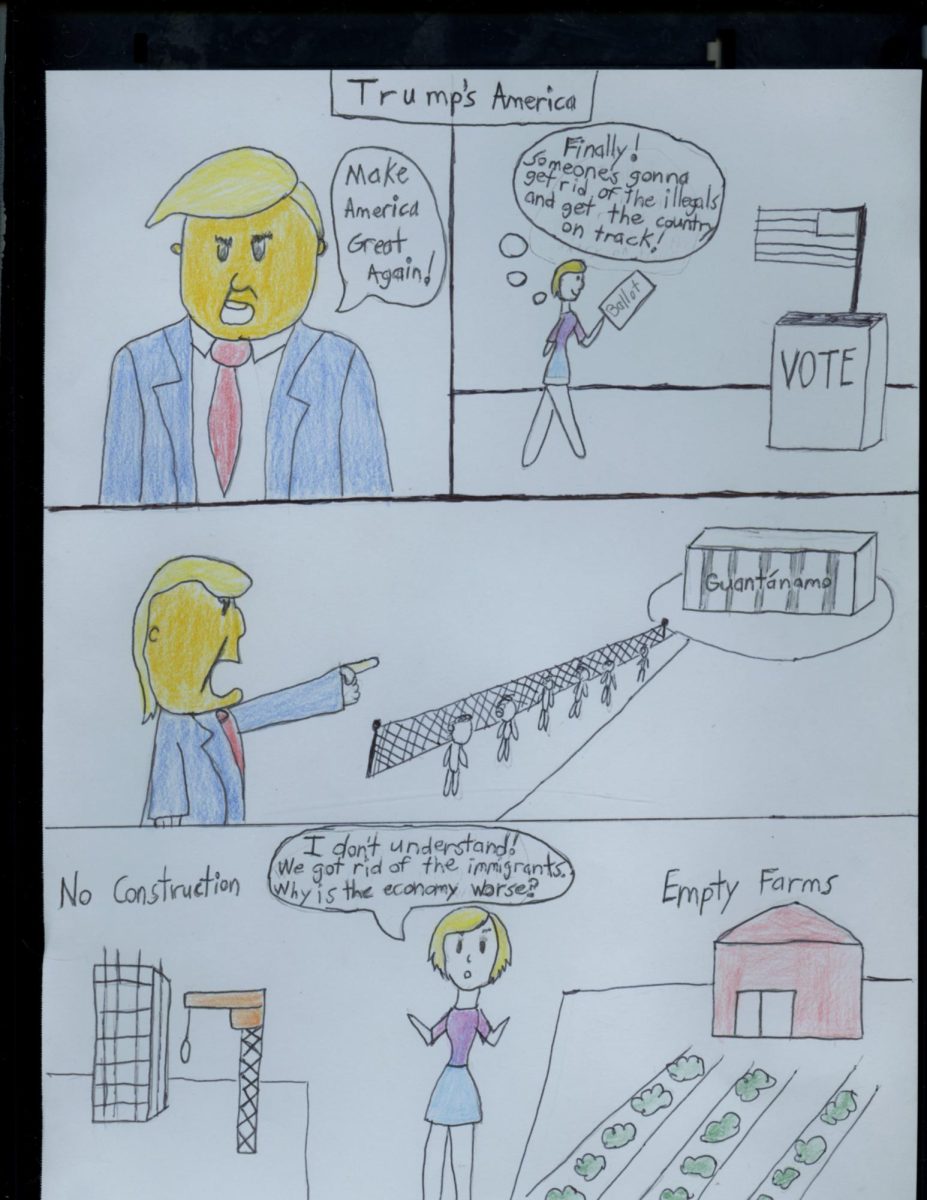

Greg Prang, an anthropology instructor, grew up on the famous eight mile road in Detroit, Michigan where he saw racism and injustice.

“Since then social justice has always been prevalent in my life. I feel like I have a justice gene and being here and talking about this is just fighting another injustice that I see,” Prang said.

Prang said he was recently diagnosed with ADHD.

“I’ve always been weird my whole life. Last year when I was taking my son for a check up, I decided to also get checked out. I self-identify as weird, not ADHD,” Prang said. “The most important thing is humanizing people, and after my diagnosis, a lot of my past makes sense now and I have gained a lot of clarity.”

In regards to his classroom design, Prang said, “As someone who probably set the record for the most incompletes at my college, I don’t give grades on assignments. I mark it as complete or incomplete and I give students multiple attempts to submit assignments. Due dates lead to doubt and self-doubt, which leads to self-destructive thoughts, and I don’t want my students to feel that way.”

“I am always thinking about political and economic limitations that students are dealing with, which has led to minorities and women not being diagnosed,” Prang said.

Omar Marquez, a sociology instructor, got his diagnosis midway through graduate school. In regards to his class rules, Marquez said, “I have no late penalties. So if a student wants to turn everything in on the last day of class, they are welcomed to. But that also means that as an instructor, I have to be ready to deal with that.”

Marquez said he utilizes a daily check in system with his students to better understand and adjust to meet their needs.

“Everyday at the start of each class, I ask students to either put up a thumbs up, sideways, or down to reflect their mood and day as a whole. I then ask some students if they are comfortable, to share why they have their thumbs in whatever direction it is and I adjust according to the needs of that day,” Marquez said.

“Assignments can’t be the only way students interact with the content. I use docs and graphics and multiple teaching styles to try and better help all students. Whether it’s physical things or sensory things, you’re just trying to better accommodate all students and keep them engaged,” Marquez said. “It’s also important to connect the content to the real world, because students are people and are dealing with real issues. You have to build relationships with students and be willing to grow.”

Austin Au, another panelist member, is a student at EvCC and said he has previously been enrolled in both Prang and Marquez’ courses.

When asked about Prang and Marquez, Au said, “They lower the pressure… This changes the way students engage in class. Oftentimes ND students are held to unrealistic expectations and there’s a lack of equality. Who would have thought students do better when they are considered?”

“Prioritizing ND (neurodivergent) students doesn’t mean you are paying less attention or taking away from others. What means the most to students is feeling like they won’t fail,” Au said.