The Long Shadow of Hysteria

EvCC staff and students discuss reproductive health issues and their fight to be heard.

Women with hysteria under the effects of hypnosis.

In the 1970s when second-wave feminism was at the forefront of the women’s rights movement, 73-year-old EvCC student Cheryl Haskins was behind the scenes fighting for her own liberation from excruciating pain.

Over the course of five years, Haskins suffered a series of reproductive issues including an ectopic pregnancy, ovarian cysts and endometriosis. Isolated in her pain with symptoms minimized by family and friends, she started to believe her ailments were conjured by her brain.

Her husband at the time suggested she just take a nice, long walk.

“You get to the point where people don’t understand or sympathize with what you’re going through, and then you think it’s all in your head,” says Haskins.

With the lack of medical knowledge at the time, it took months for a physician to determine she had an ectopic pregnancy. Her doctor first did a partial hysterectomy, leaving her with one ovary. Shortly after having her second child, the pain returned with a vengeance.

After half a decade of countless tears and trips to the hospital, she finally received relief.

Following a physician-ordered two-week waiting period where she was required to consult her husband, Haskins had a total hysterectomy to address the ovarian cysts and endometriosis.

Years of pain were brought to an end with one final procedure. “I was sick all the time. I had the flu, I had colds. After that hysterectomy, I don’t get sick anymore. My health immediately started going up.”

Her prolonged dolor reflects a dark reality many women face.

“The history of marginalizing women has played a role in our understanding of [endometriosis] and other reproductive health conditions,” says Susan Wilson of the EvCC Nursing Department. “Historically, Williams Obstetrics, a classic OB text, listed ‘hysteria’ as a potential factor in the development of endometriosis. You might also notice that the word ‘hysteria’ and ‘hysterectomy’ have the same root word; and there is a reason for that.”

The history of the “hysteric” woman is tortuous.

Plagued by beliefs that pain was intrinsic to womanhood and hysteria was the root cause of most ailments, women in pain often endured in silence. Thought to be caused by an excess or deficiency in sexual desire, women who did seek help in the 19th century were subject to treatments for hysteria including induced orgasms, removal of the clitoris or admittance to a mental hospital.

Although Western healthcare has progressed, the portrait of the hysteric woman persists. Experiences separated by decades but shared through pain, 28-year-old EvCC student Dakota McFarland dealt with similar diminishment as Haskins.

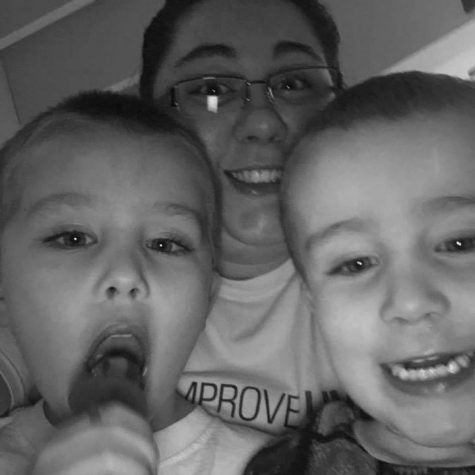

After McFarland had her second son, the symptoms began. Her story is startlingly similar to Haskins: a partial hysterectomy followed by continued pain and an uphill battle for relief.

“It was a fight to get people to listen. My doctor thought I was crazy. I kept hearing that because I have sleep apnea and I was overweight, that was what the problem was.” McFarland was then diagnosed with endometrial hyperplasia, and she fought for a year to get her second hysterectomy.

Not only women suffer from these debilitating diseases. It took Kris Taylor, a 23-year-old psychology major who identifies as trans-masculine and non-binary, several doctor visits and a switch of healthcare providers to get their official diagnosis of PCOS.

“It’s also more difficult for [my doctor] to diagnose the pelvic pain because they’re not sure if it’s just my normal anatomy causing the pain or because I am on testosterone, so that does make it a bit harder,” says Taylor.

The stories of these three people overlap in more ways than diagnoses and suffering: they all had several family members with similar ailments.

Referring to two other members of her family, Haskins said, “We all had hysterectomies when we were the same age. I had mine when I was 29, and both of them in succession had the same problems, had ectopic pregnancies and had to have hysterectomies because they had endometriosis. So, I think it kind of runs in families.”

Taylor’s sister was diagnosed with PCOS just months after their official diagnosis. McFarland’s mother also had hyperplasia.

Despite how prominent reproductive diseases are (endometriosis affects 1 in 10 reproductive-aged individuals) research on heredity is inconclusive.

Even though they span generations and gender identity, reproductive health ailments are surrounded by stigma. “You seldom hear nicknames for the brain, heart or lungs, but most of us have heard numerous nicknames for reproductive organs, which I think reflects the stigma associated with the systems, function and care that we have in our society. Sexuality and the subtopic of reproduction is seen as a ‘lesser’ or ‘baser’ human function,” says Wilson.

To find liberation from pain and stigma, McFarland says self-advocacy is crucial. “Keep pushing. We know our bodies better than any doctor is going to. If something doesn’t feel right, keep pushing.”

Which fictitious figure do you most identify with?

Fellow editor Sydney Jackson said that I am like Cher from Clueless on the outside and Wednesday...